Quantization Fundamentals for Multi-Vector Search

Multi-vector search approaches are now critical for coding agents and multi-modal applications. MixedBread, Cursor, Parallel AI, and others have enabled coding agents to use this semantic search because it cuts token usage in half, allows agents to finish tasks in half the time, and yields better-quality outputs. I’ve validated the impact on my own commercial codebases and analysis.

Multi-vector search is more powerful because it uses more contextual data from the inputs. The architecture stores a separate embedding for each word in a document, rather than the traditional approach of storing an entire document (or chunk) in a single embedding. This gives multi-vector approaches a more detailed understanding of the content, but it also means there’s a lot more embeddings.

Quantization is what makes handling this extra information practical in many cases. By representing numbers with fewer bits (like rounding to fewer decimal places), quantization trades a small amount of precision for a large reduction in storage.

This post will cover an abbreviated high level look at how these models do quantization for intuition. For additional details and full step by step walkthrough and code, check out my full step-by-step walkthrough.

Upcoming Talks on Multi-Vector Search

Modern Multi-Vector Code Search – Technical deep-dive on the multi-vector approach by mixedbread’s founder

The 1/2 Token Codebase Search – Benefits and intuition for using multi-vector search with agents to improve speed, quality, and reduce token usage.

Can’t attend live? Sign up for the talks to receive detailed writeups and recordings.

Intro to Quantization

Before diving into the advanced approach ColBERT uses (Product Quantization), let’s understand the basic concept of quantization with a simpler approach.

The most basic form of quantization is uniform scalar quantization. We can:

Take continuous values in a range

Mapping them to a smaller set of discrete levels (like 256 levels for 8-bit quantization)

Using these discrete levels to reconstruct approximations of the original values

The tradeoff is clear: we reduce storage space at the cost of some precision. With 8 bits, the error is usually very small for many applications.

Quantizing Whole Vectors

In practice it often works better to quantize vectors as a whole, instead of each number individually. This is done using a clustering algorithm like KMeans to group similar vectors. The algorithm organizes the data so that vectors with high similarity end up in the same cluster. Each cluster is then represented by a single point called a centroid. The key idea is this: instead of storing each vector’s exact values, we store two things:

The cluster ID that each vector belongs to.

The centroid value for each cluster.

When we need to reconstruct a vector, we look up its cluster ID and use the corresponding centroid as its approximation. This method provides a good balance, significantly reducing storage space while maintaining a reasonable approximation of the original data. As you might expect, there’s a trade-off: using more clusters yields a better approximation but also requires more storage for the centroids and larger cluster IDs.

This approach, often called Vector Quantization (VQ), is a solid foundation. However, to achieve high precision, it would require a massive number of centroids, making it impractical for large-scale systems. This is where we employ a more sophisticated method: Product Quantization.

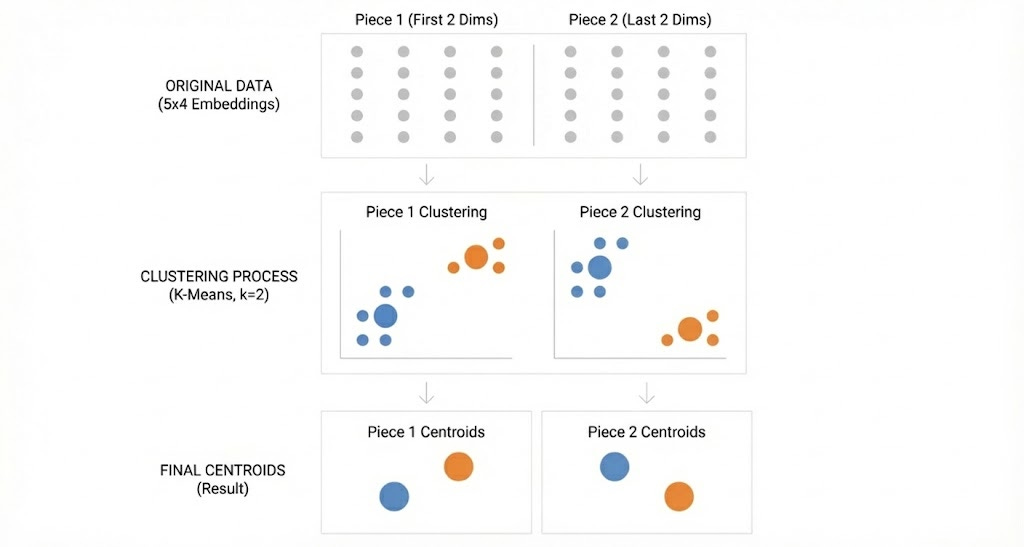

Product Quantization builds on the clustering idea but achieves far better compression by splitting each vector into smaller pieces and clustering those pieces separately. Let’s look at Product Quantization:

Step 1: Split each embedding in half.

Step 2: Cluster each collection of pieces separately.

Step 3: Store which cluster each piece belongs to.

Step 4: Reconstruct by looking up centroids and combining.

Step 5: Extreme Quantization

Extreme quantization goes a step further to store a compressed version of the “residual” (the difference between the embedding and the cluster)